All About Morning Star

Wahiev (Morning Star) or Tahmela Pashme (Dull Knife - called this by the Lakota)

1810-1883

NORTHERN CHEYENNE

Morning Star, as he was known to the Cheyenne, and Dull Knife to the Lakota, was born on the Rosebud River in present day Montana in about 1810. He was a principal chief of the Northern Cheyenne. His people called him Wahiev, which means Morning Star; however, the Lakota called him Tamela Pashme, which means Dull Knife. He acquired the name in battle with a Lakota warrior; his knife could not pierce the opponent’s tough buffalo-hide shield.

The Cheyenne system of chiefs were, forty-four consisting of four Old Man Chiefs, (Morning Star being one,) who represented all of the people, and four from each of the ten bands.

With his people’s safety in mind and hopes of gaining peace, Morning Star, (along with Little Wolf, Ohkom Kakit,) were two principle chiefs of the Cheyenne people who signed the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which promised peace between the Natives and the federal government.

Morning Star and his warriors fought in numerous campaigns, including the Colorado Cheyenne-Arapaho War (1864-65), and the War for the Black Hills, which included the Battle of the Rosebud (1876), and the Battle of the Little Bighorn 1876.

The United States wanted to build a road through Native lands in Montana because gold had been discovered in the area of Little Bighorn. In 1876, General George Custer and his men were sent to make the Native Americans give up the land, even though the U.S. had guaranteed that it belonged to them. Custer was eventually made to pay for his past actions when the Cheyenne together with the Sioux, Arapaho and Nez Perce defeated him on the battlefield at the Little Bighorn.

Following the victory over Lt. Colonel George A. Custer and his men at the Little Bighorn, the U.S. Army responded by increasing their presence in Indian territory and staging punitive expeditions. Brig. Gen. George Crook received reinforcements and began to move up the Bozeman Trail against Crazy Horse. After learning of a Cheyenne war party, he sent Col. Ranald S. Mackenzie into the Wyoming Territory to find it.

Mackenzie, with about 1,000 troopers of the U.S. 2nd Cavalry Regiment, U.S. 3rd Cavalry Regiment, U.S. 4th Cavalry Regiment, and U.S. 5th Cavalry Regiment and Pawnee warriors, found the camp. The Cheyenne warriors were having a celebration of their own because of a recent victory over the Shoshone Indians. Mackenzie waited until dawn, then attacked and drove the warriors from the village. Some were forced to leave their clothes, blankets and buffalo robes behind and flee into the frozen countryside. Morning Star began to offer stiff resistance, and savage fighting continued. The Pawnee warriors fought with exceptional ability, and the Cheyenne’s finally gave way and retreated from their village. The Indian village of 173 lodges and all its contents were entirely destroyed. About 500 ponies were captured. Lieut. J. A. McKinney, U.S. 4th Cavalry, was killed, along with five enlisted men. This time, the Northern Cheyenne surrendered, and they were sent to a reservation in Oklahoma. The Battle of Bates Creek essentially ended the Cheyenne’s ability to wage war.

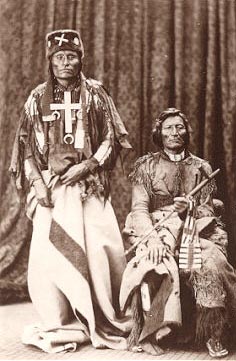

Morning Star

A band of survivors hobbled to Crazy Horse’s camp at Beaver Creek. Eleven children froze to death during the march, and the Cheyenne’s were forced to eat nearly all of their horses. Crazy Horse shared his band’s scanty food supplies and blankets but refused to rise to the invocations of some of the more hot headed Cheyenne’s to stage a last-ditch fight against the army.

“The Wasi’chus (white men) outnumber the blades of grass on the prairie,” said Crazy Horse.

“It is time to take the white man’s road…or we shall all be killed.” Morning Star agreed. “We Cheyenne’s are trying to fight the whirlwind.”

In spring 1877, the Cheyenne’s who had lodged with Crazy Horse during the winter surrendered to General Nelson Miles at Fort Keough. About thirty young warriors, those who had felt betrayed by Crazy Horse’s refusal to aid them in a last-ditch battle, enlisted as scouts for Miles against Crazy Horse’s band, which were still free. The rest were sent to Darlington Reservation in Indian Territory. Within two months of their arrival, two-thirds of the tribe became sick and many died. Chief Morning Star and other leaders pleaded for a reservation for their own people back in Montana, but the U.S. refused them. The Darlington Reservation land was worthless, the buffalo were gone, and those sent to the reservation previously had hunted smaller animals to virtual extinction. Conditions were so unhealthy that a sickness, most likely cholera, infected more than half of the weary and malnourished Cheyenne. Some succumbed to the fever while others starved to death.

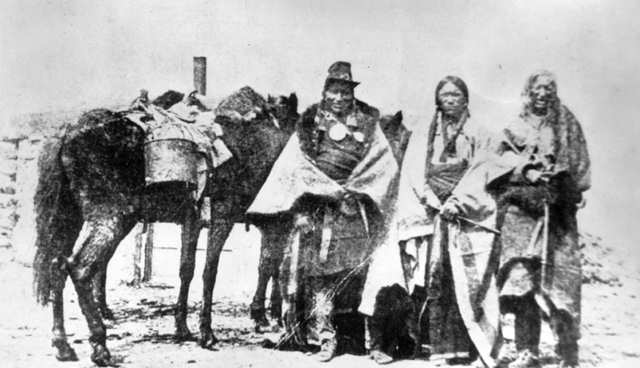

Cheyenne Warriors

Fearing for his people, Morning Star realized with growing bitterness that promises of abundant game in Oklahoma were a lie. The buffalo were gone, and smaller game had been hunted to near extinction by the Indians who had been sent there earlier. Cheyenne’s began to die of a fever, probably malaria; others starved. Promised government rations did not arrive on time. In the middle of August 1878, Morning Star and Little Wolf pleaded with Indian agent John Miles to let the Cheyenne’s return home to Montana. Half the band had died in their year in Oklahoma. Morning Star himself was shaking with fever as they talked. Miles asked for a year to work on the problem, and Little Wolf told him the Cheyenne’s would be dead in a year. Miles refused to relent. The next morning at sunrise, the three hundred surviving Cheyenne’s, 89 warriors, and 246 women and children, broke for the open country, heading for their home on the Powder River, a thousand miles away.

On the 17th September 1878, Morning Star’s band of northern Cheyenne’s attacked the cattle camps south of Fort Dodge, where they killed several white men and drove off some of the cattle. News of the event reached Governor Anthony the next day and he appealed to General Pope, commanding the department, but Pope thought it was nothing more than a “scare.” The governor sent Adjt.-Gen. Noble to Dodge City with arms and ammunition, but the Indians had moved on northward. Lieut.-Col. William H. Lewis, with a detachment of troops from Fort Dodge, pursued the Indians and came upon them at a canyon on Famished Woman’s fork. In the fight that ensued Lewis was killed. Telegrams from various points in the western part of the state poured into the governor’s office appealing for aid, but still Gen. Pope declined to act.

Captured Cheyenne at Dodge City, Kansas, spring 1979 to be tried for murder.

Top: Tangle Hair, Left Hand, Old Crow, Porcupine. Bottom: Wild Hog, George Reynolds (interpreter),

Noisy Walker, Blacksmith

Photograph from Kansas State Historical Society

Grave of Morning Star (left) and Little Wolf, Lame Deer Montana

Present Day Marker

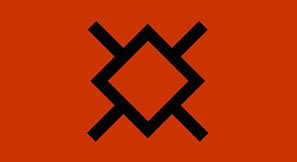

The current day flag of the Northern Cheyenne is located on the left. The symbol you see represented at the centre is that of the morning star, which was the emblem of Chief Morning Star. The morning star glyph was also used during the Sun Dance, when the warriors would paint it on their chests for the ceremony. The ancient version of this flag wasn’t blue in color, but a deep reddish brown, with the morning star glyph painted in black similar to the one above on the right.

Morning Star and Little Wolf Graves